Olara Otunnu: 2005 Sydney Peace Prize Address

Saving our children from the scourge of war: The Sydney Peace Prize 2005

9 November 2005

I.

|

|

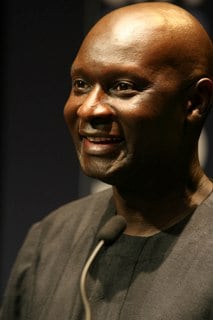

Olara Otunnu delivers the 2005 Sydney Peace Prize lecture |

Tribute and Dedication

If I may, I should like, first of all, to express my heartfelt and humble appreciation to the Sydney Peace Foundation for selecting me to be the recipient of the Sydney Peace Prize for 2005. I am greatly honoured by this award, all the more so as I am following in the footsteps of a very eminent group of international leaders and statesmen – – Professor Muhammad Yunus, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, President Xanana Gusmão, Sir William Deane AC KBE, Mary Robinson, Dr Hanan Ashrawi, and Arundhati Roy. I pay warm tribute to my predecessors for being courageous champions of freedom, dignity and human rights for all. I feel privileged to know and to count several of them as my friends.

As I look back on the long road we have travelled in the campaign to save children being destroyed by wars, my thoughts go particularly to many people that I have been very fortunate to meet during my visits to zones of conflict – – these ‘ordinary people’ (as the world would call them), doing extraordinary things, in impossible circumstances. Out of the ugliness, hatred and desolation visited upon them by the lords of war, these unsung heroes have reclaimed the core and beauty of the human spirit. I have been deeply inspired and humbled by their example of faith, selfless giving and sacrifice, and sheer courage, in the face of overwhelming odds.

These women, men and children, whose names we often do not know, who do not participate in our conferences and deliberations, nor do they generally feature in our reports –their contribution places into perspective our own very modest efforts. Today I remember and honour them. I think, for example, of:

— the very poor but incredibly generous host families in Kukes (Albania) and Tetovo (F.Y.R. of Macedonia), spontaneously opening their homes and hearts to children and their parents fleeing from Kosovo in 1999;

— the women in Kuku and Yei camps for displaced persons in Juba (Sudan), building makeshift huts and improvised schools for their children, rejoicing and singing songs of praise with such faith and courage;

— Maggie and Beatrice in Ruiigi (Burundi), caring for all orphans across the Tutsi-Hutu divide;

— Dr. Paul Tingwa (coincidentally my schoolmate at Budo and university roommate at Makerere), the medical doctor, who has held out for years, running the only functioning hospital in a war zone of southern Sudan;

— Mama Roselyn in Gisenyi taking care of orphans; and the many girls who suddenly faced the daunting task of heading some 40,000 households in the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda;

— the brave women and elders of Bunia, and the dynamic civil society leaders in Bukavu (DRC);

— the volunteer teachers in Soacha and Turbo (Colombia) struggling to provide improvised schooling to children who are so lively and thirsty for knowledge;

— the children’s movement campaigning to end the war in Colombia;

— the group of boys and girls in Northern Ireland, each of whom has lost a parent to sectarian violence, but who have come together to advocate tolerance and reconciliation between Catholics and Protestants;

— the University Teachers of Jaffna (Sri Lanka), putting their lives on the line in order to monitor and report on grievous violations against children;

— Engineer Ahmad of the Aschiana Center (Afghanistan) and Padre Horaçio of the Hernaldo Jansen Center (Angola) giving hope to street children;

— Annalena Tonelli, the Italian humanitarian worker, who was murdered in Somalia in 2003, after more than three decades of devoted service to children and education;

— the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, which has kept faith with the people, and continues to struggle, against all odds, for the end to genocide and war in northern Uganda.

I could go on, and on. These local heroes deserve much more recognition and support from the international community. Let us listen to them. Let us learn to walk more closely along their side.

And I hope that their example will spur us beyond the complacency of lip service, into real action for children, that it will challenge us to rise above the parochial and political considerations that all too often trump the best interests of children, and that it will move us to join hands among ourselves and with them in a common spirit and a common struggle to save our children from the scourge of war.

That is why I should like to dedicate this award to these unsung local heroes, these defenders of children who are serving at the frontline of this struggle.

I am also pleased to inform you that the Sydney Peace Prize for 2005 and another prize I had received earlier (the German Africa Prize) have served as catalysts and encouragement in the formation of a new independent organization – – LBL Foundation for Children – – that will be launched soon, and devoted to providing hope, healing and education for children in communities devastated by war. The monetary values which accompany the two awards will also serve as seed money for the new organization. The foundation will concentrate primarily on the following targeted activities:

— Global advocacy to promote and support the ‘era of application’ for the protection of war-affected children, focusing particularly on support the full implementation of the measures contained in the compliance regime adopted by the UN Security Council in Resolution 1612 (July 26, 2005)

— Raising the level of awareness and focus about particular conflict situations, where children are gravely affected, but which remain largely neglected by the international community; and, in this context, mobilize support and resources for the children and communities in distress.

— Supporting local communities to build their own capacities for advocacy, protection, assessment and rehabilitation; and, in this context promoting systematic exchange of ‘lessons learned’ and ‘best practice’ for the rehabilitation of children.

Thus the new foundation will combine global advocacy for war-affected children with concrete action in particular situations; in the latter, initially focusing on one important situation, which could also serve as a template for further engagement and action.

The theme I have chosen for the public lecture today is: Saving our children from the scourge of war. I believe that few missions could be more compelling for the world today.

II. A campaign to save our children from the scourge of war

When adults wage war, children pay the highest price. Children are the primary victims of armed conflict. They are both its targets and increasingly its instruments. Their suffering bears many faces, in the midst of armed conflict and its aftermath. Children are killed or maimed, made orphans, abducted, deprived of education and health care, and left with deep emotional scars and trauma. They are recruited and used as child soldiers, forced to give expression to the hatred of adults. Uprooted from their homes, displaced children become very vulnerable. Girls face additional risks, particularly sexual violence and exploitation.

All non-combatants are entitled to protection in times of war. But children have a special and primary claim to that protection. Children are innocent and especially vulnerable. Children are less equipped to adapt or respond to conflict. Children represent the hopes and future of every society; destroy them and you have destroyed a society.

The scope of this scourge is worldwide and widespread. Consider the following. Over 250,000 children continue to be exploited as child soldiers – – used variously as combatants, porters, spies and sex slaves. Tens of thousands of girls are being subjected to rape and other forms of sexual violence, including as a deliberate tool of warfare. Abductions are becoming widespread and brazen, as we have witnessed, for example, in Northern Uganda, Nepal and Burundi. Since 2003, over 11.5 million children were displaced within their own countries, and 2.4 million children have been forced to flee conflict ad take refuge outside their home countries. Approximately 800 to 1000 children are killed or maimed by landmines every month. In the last decade, over 2 million children have been killed in conflict situations, over 6 million have been seriously injured or permanently disabled. As the horror of Beslan (Russian Federation) and other incidents have recently demonstrated, schools are increasingly being targeted for atrocities and abductions.

The magnitude of this abomination attests to a new phenomenon. There has been a qualitative shift in the nature and conduct of warfare.

This transformation is marked by several developments. Almost all the major armed conflicts in this world today are internal; they are unfolding within national boundaries and typically are being fought by multiple semi-autonomous armed groups. These conflicts are characterized by a particular brand of lawlessness, cruelty and chaos. In particular, they are defined by the systematic and widespread targeting of civilian populations. In the intense and intimate setting of today’s internecine warfare, the village has become the battlefield and civilian populations the primary target. The purpose of war has shifted from overpowering the enemy army, to the annihilation of a so-called ‘enemy community.’ These conflicts tend to be protracted, lasting years if not decades, often in recurring cycles, thus exposing successive generations of children to horrendous violence. Most cynically, children have been compelled to become themselves the instruments of war – – indeed the weapon of choice – -recruited or kidnapped to become child soldiers. Another feature of these conflicts is the proliferation of light-weight weapons that are easily assembled and borne by children.

I can think of no group of persons more completely vulnerable than children exposed to armed conflict. Yet, until very recently, their fate did not engender specific and systematic focus and response by the international community. This has changed.

At the end of 1996, the UN General Assembly received a commissioned report by Graça Machel on the impact of armed conflict on children. This followed three years of worldwide survey, consultations and analysis. An important outcome of Graça Machel’s report was the creation of the mandate of Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict. I wish to pay special tribute to Graça Machel, whose seminal report laid a strong foundation for the mandate on CAAC .

Over the last several years, I have led a UN-based campaign to mobilize international action on behalf of children exposed to war, promoting measures for their protection in times of war and for their healing and social reintegration in the aftermath of conflict. I undertook this mission by developing and implementing specific strategies, actions and initiatives. These were organized in three phases, namely: laying the foundation; developing concrete actions and initiatives; and instituting the ‘era of application.’

Laying the foundation

The first phase — laying the foundation — consisted of defining and framing the CAAC agenda, gaining acceptance and legitimacy for that agenda, establishing a network of stakeholders within and outside the UN, and laying the groundwork for broader awareness- raising and advocacy.

Developing concrete actions and initiatives

In the second phase –developing concrete actions and initiatives — I spearheaded collaborative efforts (involving in particular UN entities, governments, NGOs and regional organizations) to develop concrete actions and initiatives. These initiatives and advocacy yielded significant advances and innovations, most notably: there has been significant rise in awareness, visibility and advocacy of CAAC issues; the protection of war-affected children has been firmly placed on the international peace-and-security agenda; a comprehensive body of protective instruments and standards has now been put in place ; a systematic practice of obtaining concrete commitments and benchmarks from parties to conflict has been developed; children’s concerns are being included in peace negotiations and accords, and have become a priority in post-conflict programmes for rehabilitation and rebuilding; Child Protection Advisers (CPAs) have become part of peacekeeping operations; key regional organizations have incorporated this agenda into their own policies and programmes; CAAC issues have been integrated and mainstreamed in institutions and mechanisms, within and outside the UN; war-affected children are coming into their own, through their active participation in advocacy and rebuilding peace; child protection provisions are now systematically included in the mandates, training and reports of peacekeeping missions; many local initiatives for advocacy, protection, and rehabilitation have been developed; other innovations include the establishment of National Commissions for Children in post-conflict situations, the ‘Voice of Children’ radio projects for children and by children, and the establishment of the International Research Network on Children and Armed Conflict. These efforts have created strong momentum.

Instituting the ‘era of application’

In spite of these impressive gains, I was deeply troubled by one phenomenon. On the one side, we had developed these clear and strong standards for the protection of CAAC, and important concrete initiatives, particularly at the international level. On the other side, atrocities and impunity against children continued largely unabated on the ground. In effect, the international community and the children were now faced with a cruel dichotomy.

To my mind, the key to overcoming this gulf lay in instituting a systematic campaign for the ‘era of application’ — the application of international instruments and standards on the ground. Words on paper alone cannot save children and women in danger.

I spent the last three years, working to crack this nut – – developing, designing, drafting, and consulting with stakeholders (governments, UN agencies, regional organizations, and NGOs) – – a series of measures to constitute the ‘era of application’. These efforts culminated in concrete, detailed and formal set of proposals – – compliance measures – – submitted to the Security Council last January. After six months of intensive and protracted negotiations within the Security Council and with other delegations, in a major and ground-breaking development, the UN Security Council on July 26 unanimously adopted Resolution 1612, endorsing the series of far-reaching measures designed to institute a serious, formal and structured compliance regime for the protection of children exposed to war, which I had proposed at the beginning of the year. This is a turning point of immense consequence.

The compliance regime contained in Resolution 1612 is the first of its kind and breaks new ground in several respects.

First, it establishes a ‘from-the-ground-up’ monitoring and reporting system, which will gather objective, specific, and timely information – – ‘the who, where and what’ – – on grave violations being committed against children in situations of armed conflict. UN-led task forces in conflict-affected countries will focus on six especially serious violations against children: killing or maiming; the recruitment or abduction of children for use as soldiers; rape and other sexual violence against children; attacks against schools or hospitals; and the denial of humanitarian access to children.

Second, all offending parties, governments as well as insurgents, will continue to be identified publicly, in what has been called the ‘naming and shaming’ list submitted annually to the Security Council since 2003. The latest report lists 54 offending parties in 11 countries. These include: the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka; FARC in Colombia; the Janjaweed from Sudan; the Communist Party of Nepal; the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda; the Karen National Liberation Army in Myanmar; and government forces in DRC, Myanmar and Uganda.

Third, the Security Council has ordered offending parties, working in collaboration with UN Country Teams immediately to prepare and implement very specific action plans and deadlines for ending the violations for which they have been listed. Typically, these should include: immediate end to all violations by the listed party; commitment by the listed party to the unconditional release of all children within its ranks, within a time-frame agreed with the United Nations team; time-bound plan and benchmarks for monitoring progress and compliance, agreed with the United Nations team; and agreed arrangements for access by the United Nations team for monitoring and verification of the action plan.

Fourth, where parties fail to stop their violations against children, the Security Council will consider targeted measures against those parties and their leaders, such as travel restrictions and denial of visas, imposition of arms embargoes and bans on military assistance, and restriction on the flow of financial resources.

Fifth, to monitor and assess progress on this issue, the Security Council has established its own Working Group to oversee compliance with all the elements of Resolution 1612.

Clearly, the compilation of information on violations and the listing of offending parties have little value unless they serve as triggers for action, beginning with the Security Council and other decision-making bodies. However, it is crucial that this issue be taken up beyond the corridors of the United Nations, by the concerned public at large. That is why we need a major international public campaign for compliance. With Resolution 1612 we have a solid base and springboard for this campaign, particularly by legislators, religious leaders, women’s organizations, the media, non-governmental organizations, and children themselves.

Building local capacity for protection and rehabilitation

In order to build a viable regime of protection on the ground, international actors need to support and reinforce local efforts. In particular, we need to do much more to strengthen the capacities of defenders of children who are labouring at the very frontline of this struggle – – national institutions and local and sub-regional civil society networks for advocacy, protection, and rehabilitation. This is the best way to ensure local ownership and long-term sustainability for the protection of children.

I believe that we should strongly support local communities in their efforts to reclaim and strengthen indigenous cultural norms that have traditionally provided for the protection of children and women in times of war. In addition to international instruments and standards, various societies can draw on their own traditional norms governing the conduct of warfare. Societies throughout history have recognized the obligation to provide children with special protection from harm, even in times of war. Distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable practices have been maintained, as have time-honoured taboos and injunctions prohibiting indiscriminate targeting of civilian populations, especially children and women. These traditional norms provide a ‘second pillar of protection’, reinforcing and complementing the ‘first pillar of protection’ provided by international instruments.

Can we influence insurgents?

The question is often raised as to how the international community can influence the conduct of all parties to conflict, particularly insurgents. In fact, insurgent groups have grown increasingly sophisticated in their political and financial operations and in their external connections. This means that carefully chosen and calibrated measures can have significant impact on insurgencies.

The imposition of carefully calibrated and targeted measures can have the desired impact on governments as well as insurgents. At political and practical levels there are levers of influence that can have significant sway with all parties to conflict. In today’s world, parties in conflict do not operate as islands unto themselves. The viability and success of their political and military projects depend crucially on networks of cooperation and goodwill that link them to the outside world – – to their immediate neighbourhood as well as to the wider international community. In this context, the force of international and national public opinion; the search for acceptability and legitimacy at national and international levels; the demand for accountability as represented, for example, by the ICC and ad hoc tribunals; the external provision of arms and financial flows; and illicit trade in natural resources; the growing strength and vigilance of international and national civil societies, and media exposure – – all of these represent powerful conditions and means to influence the conduct of parties in conflict. From this list, “pressure points” can be determined and a customized and precise sanction regime can be constituted against a given offender. That the imposition of such carefully calibrated and targeted measures can have the desired impact on insurgents as well as governments is demonstrated by the recent examples of effective sanctions measures imposed on UNITA in Angola and RUF in Sierra Leone.

III. SOS Northern Uganda — profile of a genocide

As we meet here today to focus on the fate of children being destroyed in situations of war, I must draw your attention to the worst place on earth, by far, to be a child today. That place is the northern part of Uganda.

What is going on in northern Uganda is not a routine humanitarian crisis, for which an appropriate response might be the mobilization of humanitarian relief. The human rights catastrophe unfolding in northern Uganda is a methodical and comprehensive genocide. An entire society is being systematically destroyed – -physically, culturally, socially, and economically – – in full view of the international community. In the sobering words of a missionary priest in the area, “Everything Acoli is dying”. I know of no recent or present situation where all the elements that constitute genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) have been brought together in such a comprehensively and chilling manner, as in northern Uganda today.

The situation in northern Uganda is far worse than that of Darfur, in terms of its situation, its magnitude, the scope of its diabolical comprehensiveness, and its long-term impact and consequences for the population being destroyed. For example, Darfur is 17 times the geographic size of northern Uganda and 4 times the size of its population, yet northern Uganda has had 2 million displaced persons for 10 years, the same as the number of displaced persons in Darfur today. The situation in Darfur has lasted for 2 ½ years now; the tragedy in northern Uganda has gone on for 20 years now, with the forced displacement and concentration camps having lasted now for 10 years. I applaud the attention and mobilization being focused by the international community on the abominable situation in Darfur. But what shall I tell the children of northern Uganda when they ask: how come the same international community has turned a blind eye to the genocide in their land?

How shall I explain to the perplexed children that those on whom they had counted to defend their human rights have instead become the cheerleaders and chief providers of succour and support for a regime which that is presiding over genocide, a regime which celebrates systematic repression, ethnic discrimination and hatred, impunity and corruption, under 20 years of one-party rule, a regime which routinely and chillingly gloats about destroying “those people” – – “those people” and their children? The emperor has no clothes but these terrifying fragments.

As it happens, last September, world leaders meeting at the special UN summit in New York adopted an important declaration on “Responsibility to Protect.” They have made a solemn commitment to act together to protect populations exposed to genocide and grave dangers, when their own government is unable or unwilling to protect them, or, worse, when the state itself is the instrument of a genocidal project. This has been precisely the situation in northern Uganda for twenty years. But for those 20 years, political considerations have trumped “responsibility to protect.” And in that calculus, the children and women of northern Uganda have become literally expendable.

The genocide in northern Uganda presents the most burning and immediate test case for the solemn commitment made by world leaders in September. Will the international community on this occasion apply “Responsibility to Protect” objectively, based on the facts and gravity of the situation on the ground, or will action or inaction be determined by ‘politics as usual’?

Witness the following:

• This human rights and humanitarian catastrophe in northern Uganda has been going on, non-stop, for twenty years.

• For over 10 years, a population of almost 2 million people have been herded into concentration camps (some 200 camps in all), having been forcibly removed from their homes and lands by the government. Such en masse forced displacement and instrument is reminiscent of similar exercises conducted in apartheid South Africa and Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia. Today virtually the entire population of Acoli (95%) is in these concentration camps, in abominable conditions – – massively congested with woeful sanitation and rampant with diseases. As one elder summarized it, “People are living like animals.”

• According to a recent conservative estimate, 1,000 people die in these camps per week; this means 4,000 lives every month, and about 50,000 deaths every year. This does not include those who have been killed in outright atrocities.

• These camps have the worst and most dramatic infant mortality rates anywhere in the world today.

• Chronic malnutrition is widespread; 41% of children under 5 years have been seriously stunted in their growth.

• Two generations of children have been denied education as a matter of policy, they have been deliberately condemned to a life of darkness and ignorance, deprived of all hope and opportunity. Imagine this is the land that produced Archbishop Janani Luwum (the celebrated 20th century martyr), Professor Okot p’Bitek (the philosopher poet) and Professor G. W. Odonga (the renown surgeon); they are among Africa’s gifts to the world.

• For a society which has been so renowned for its deep-rooted and rich culture, values system and family structure, all three have been destroyed under the weight of the conditions systematically imposed in the camps. This loss is colossal; it signals the death of a society and a civilization.

• In the face of relentless cultural and personal humiliations and abuse, suicide, serious depression and alcoholism have become rampant.

• Rape and generalized sexual exploitation, especially by soldiers, have become “entirely normal.” In Uganda, HIV/AIDS has become a deliberate weapon of mass destruction. Soldiers who have tested HIV-positive are then especially deployed to the north, with the mission to commit maximum havoc on the local girls and women. Thus from almost zero base, the rates of HIV infection among these rural communities have galloped to dramatic levels. This, even as official propaganda touts Uganda’s example the model for the fight against HIV/Aids!

• The population has been deprived of all means of livelihood; they have been denied access to their lands, while the entire mass of their livestock was forcibly confiscated and simply exported from the north.

• Over the years, thousands of children have been abducted by the LRA.

• Some 40, 000 children, the so called “night commuters,” trek many hours each evening to reach the towns of Gulu and Kitgum (and walk back the same distances in the morning) to avoid abduction by the LRA.

• The population has been rendered totally vulnerable; they are trapped between the gruesome violence of the LRA and the genocide atrocities, humiliations are being systematically committed by the government.

• Incidentally, the society and civilization that is now being destroyed in northern Uganda, in the people and culture that produced me. I am what I am today largely because of that background. Otherwise I would almost certainly not be here to receive the Sydney Peace Prize today. The thought of that society and its incredible heritage being deliberately destroyed was at first unthinkable, and now it is simply unbearable.

The grim facts outlined above are well known in foreign chancelleries, UN agencies, international NGOs and human rights organizations. Yet, with a few exceptions, those in a position to raise their voices and to act have instead joined in a conspiracy of silence. This betrayal is all the more painful because it has come from the very governments and organizations they had counted on to mount a vigorous defence of their human rights. We have applauded these governments for making the values of human rights, democracy, good governance and accountability a cornerstone of their international policy, and yet concerning the cynical and consistent negation of these values in Uganda, they have adopted a policy of “We see no evil, we hear no evil”.

There is need for a very, very deep soul-searching about what has been going on in Uganda. The Ugandan situation and the response to it – – or rather the conspicuous lack of response thereto – – raises some very disturbing questions about the discourse and the application of human rights policies by the international community.

Today, from this podium and on this important occasion of the award of the Sydney Peace Prize, I wish to address a most urgent appeal – – a cri de coeur – – to the leaders of the western democracies in particular, concerning the genocide in northern Uganda. It is with a heavy and anguished heart that I do so. But I must do so for the sake of the children and in the name of the 2 million people being destroyed in the 200 camps of death of humiliation.

We must retrieve the path of a principled application of human rights. There must be one set of human rights for all victims, or we undermine human rights discourse for all victims. When human rights are applied selectively, we reap a whirlwind of cynicism.

We must denounce and stop genocide wherever it occurs, regardless of the ethnicity or political affiliation of the population being destroyed.

For the sake of the children, and the 2 million people in the concentration camps, I appeal to the western democracies to review their continued sponsorship and support for a regime that is orchestrating and presiding over the genocide of its own population.

I wonder if we have learned any lessons from history. When millions of Jews were exterminated during the Holocaust in Europe, we said ‘never again,’ – – but after the fact. When genocide was perpetrated in Rwanda, we said ‘never again,’ – – but again after the fact. When children and women were massacred in Srebrenica, we said ‘never again,’ – – but after it was all over. The genocide unfolding in northern Uganda is happening on our watch, and with our full knowledge. Why is there no action?

And so, what shall I then tell the children of northern Uganda – – when they ask about the dark deeds that is stalking their land and devouring its people? What will it take, and how long will it take, for leaders of the western democracies in particular to acknowledge, denounce and take action to end the genocide unfolding in northern Uganda? And tomorrow, shall we once gain be heard to say that we did not know what was going on? That for all these years we were unaware of the dark deeds being conducted in northern Uganda.

IV. Conclusion

When the tsunami tragedy struck in Asia and the recent earthquake ravaged the countries of South- Asian countries, we felt almost entirely helpless, in the face of a mighty fury unleashed by the force of nature. Alas, what is happening to children in many conflict areas is a wholly human-made catastrophe. This is nothing short of a process of self-destruction, consuming the very children who assure the renewal and future of all our societies. How can we allow this? Unlike the onslaught of the tsunami yesterday, we can do something today to bring an end to this man-made horror – – the horror of war being waged against children and women.

As we discuss today what measures to take for the protection of children, I can hear Bob Marley, with his spiritual rendition of the themes of suffering and redemption for those who are vulnerable and abused.

I can hear Bob Marley challenging us, singing:

`Hear the children cryin’

Hear the children cryin’

From Beslan to Bar-Lonyo to Bunia

And so we tell them:

No, children, no cry

Don’t worry about a thing, oh no!

‘Cause everything gonna be all right.Hear the children cryin’

From Mazar-i-Sharif to Jumla to Darfur

Won’t you help to sing

‘Cause all they ever asked:

Redemption Songs. Redemption Songs.Rising up this mornin’,

I saw three little birds

Pitch by the doorstep of the Security Council

Singin’ sweet songs

Of melodies pure and true,

Sayin’, This is our message to you-ou-ou.Hear the children cryin’

From Apartado to Malisevo to the Vanni

But I know they cry not in vain

‘Cause now the times are changin’

Love has come to bloom again.

Well, the children are waiting – – they are waiting for the Redemption Songs.

Recent Comments